Adventures with InfoGANs: towards generative models of biological images (part 1)

I recently began an AI Residency at Google, which I am enjoying a great deal. I have been experimenting with deep-learning approaches for a few years now, but am excited to immerse myself in this world over the coming year. Biology increasingly generates very large datasets and I am convinced that novel machine-learning approaches will be essential to make the most of them.

At the beginning of my residency, I was advised to complete a mini-project which largely reimplements existing work, as an introduction to new tools. In this post I’m going to describe what I got up to during that first few weeks, which culminated in the tool below that conjures up new images of red blood cells infected with malaria parasites:

I’m going to try to explain it from first principles, which might take a while, so if you have a background in machine-learning, skip to the next post.

Neural net-what?

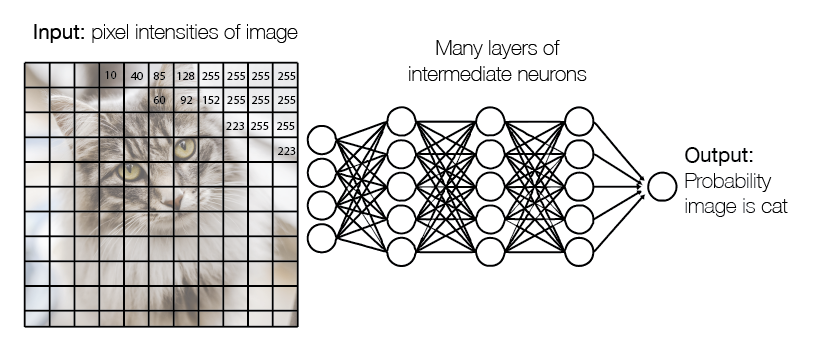

Deep learning is based around things called neural networks. A neural network takes a series of numbers in, does some processing to them, and ultimately spits out another set of numbers. A system like this is in theory capable of undertaking a great many tasks: for example the first series of numbers could be the brightness values for each pixel in an image, and the number outputted could be the probability that the image contains a cat. If the network can map those sets of numbers to each other successfully, then you have a cat-recognition network.

But what determines whether the network will recognise cats, koalas, or fail to recognise anything at all? Each network contains a vast array of parameters, which determine how the input numbers are processed to produce the output. These are knobs which can be twiddled to make the network do different things.

The magic that makes neural networks powerful is a process called back-propagation, which allows the system to automatically twiddle these knobs until the network produces the desired output for each input. This requires a large amount of labelled data. For our cat network we might give it 1,000 photos of cats, and 1,000 photos of dogs. The system will start off by setting the parameters to random values. It will then feed in the first cat photo and see what number it gets out. With these random values, the network will most likely output 0.5 as the cat probability, even though the true value is 1 (it’s a cat!). But with back-propagation the system can observe this error (0.5 – 1 = -0.5) and calculate which direction it needs to turn each knob (and by how much) to make the error smaller. If we repeat this process over and over and over again (which is called training), we will eventually we find we have a network that can reliably distinguish cats and dogs. And it turns out that the graphics cards in our computers can be commandeered to make that process happen pretty quickly. In an hour or so we can have our cat recognition network – jubilations.

With those basic principles one can build a network to do any sort of classification problem. If you have searched your own photos based on what they contain (e.g. on Google photos) then you have interacted with just such a network.

Making computers creative

You might think at this point that our network has a pretty good idea what a cat looks like, but unfortunately with this approach you can’t ask it to draw one.

One can imagine a neural network which could draw, however: this time the output would be a series of numbers, which we will convert into to the brightness values of pixels in an image. What should the input be? It turns out we can just use random numbers: for each image we can sample say 10 values from a normal distribution, and feed them in. That way, in theory, the network can draw on this randomness to generate a different picture each time, and act as an image generator.

There is a problem of course. The network still has no idea what cats look like. When it is created, with its knobs set to random positions, it will generate images that resemble those on an un-tuned TV. In theory we could train it ourselves, by letting it know whenever it produced noise that had the faintest of resemblance to a cat, until it was coaxed into doing what we wanted. In practice however, this would take an eternity.

So what to do? Well, there’s a trick, invented just four years ago, which has been revolutionary. We can introduce a second network, called a discriminator. This is a classification network, like the one we imagined above. But this time its task is not to distinguish cats from dogs, but to distinguish real photos of actual cats, from fake cats imagined by the generator. We feed it some real cats, and some fake ‘cats’ that the generator has produced, and we train it. Initially it has a very easy job here, since remember the generator is just displaying the images of an untuned TV. But wait..

Once the discriminator starts to do a decent job we can take our back-propagation one step further. The system can backpropagate from the final result (“fake” or “real”) back to the pixel values produced by the generator, and then all the way back through the generator to the random variables that made these fake images. Then it can ask “what directions should I turn the knobs of the generator so that it produces an output that the discriminator thinks is real?”. In this way, the generator can be trained to fool the discriminator, and in doing so, the images it produces will become a bit more cat-like.

The discriminator can now be trained again, to be more expert in telling these synthetic cats from their real counterparts. In fact we bounce back and forth, training generator and then discriminator in a continual loop. They have opposing goals, the generator wants to make realistic cat images and the discriminator wants to tell these apart from true cat images, and so this architecture is called a generative adversarial network or GAN. After a long period of training these networks can produce results like these:

Not bad, eh?

InfoGAN – images that communicate information

This approach can produce realistic images. But the relationship between the random noise at the beginning and the image at the end is not generally clear. If we increase value 3 by 50% what will happen? It is generally difficult to predict, and does not correspond in a useful way to a semantically meaningful property of the image.

There would be a lot of value to a network which, without being specifically trained to, could actually understand the structure in these images (e.g. that there are different breeds of cat) and that at the end could generate an image of any breed of your choice.

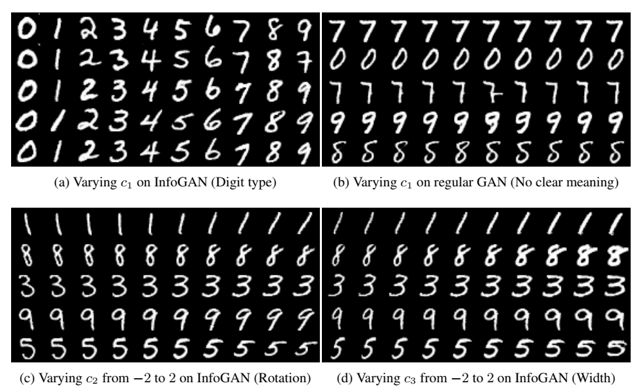

Some people came up with a very clever way of doing this, called an InfoGAN. This approach is very similar to the original GAN. The generator still draws on random noise to produce its image. However the generator is also given some extra noise, which it is tasked with encoding into the image it produces. For instance in the original InfoGAN paper the researchers produced a network which made images of hand-written digits. The extra noise they added was a discrete ‘one-hot’ variable with ten possible values. The idea was to create a network where each of these values corresponded to a different digit. To get this to happen they created an additional training objective for both the generator and the discriminator. As before, the discriminator still wants to distinguish real images from fake images and the generator still wants to fool the discriminator. However both the discriminator and the generator are also rewarded if the discriminator is able to successfully reconstruct the extra random variable that was fed to the generator.

This means the generator now has to encode information (a variable with ten possible values) into an image, but that image has to be a plausible member of the set of hand-written digit images. The strategy that it ends up taking is to encode each value as a separate digit, and tada, we have achieved our goal. We can now ask the network to generate any specific digit we like. We can choose threes and generate an infinite number of different threes in different styles. The researchers also showed that if they added two more continuous variables to be communicated, these ended up mapped to the angle, and the width, of the digit produced.

I began by reimplementing some of what these researchers had achieved, focusing on this hand-written digit task. Here are the images my network produced evolving over time:

You can see the network gradually deciding how it will encode each value. It is undecided about what should be a five and what should be a zero for a long time, but it eventually comes to a conclusion. So without labelling any of the data, the system has learnt to partition it into ten appropriate categories, and has built a system for arbitrarily generation members of each of these categories.

There are a near-infinite number of possible threes that can be drawn – cleaner or curlier, thicker or thinner, but all are united in being threes. I think that a very similar property applies in biological cells and in the next post I’ll describe my forays into this area, and the promise I think such an approach holds.