COVID-19 and the categorical imperative

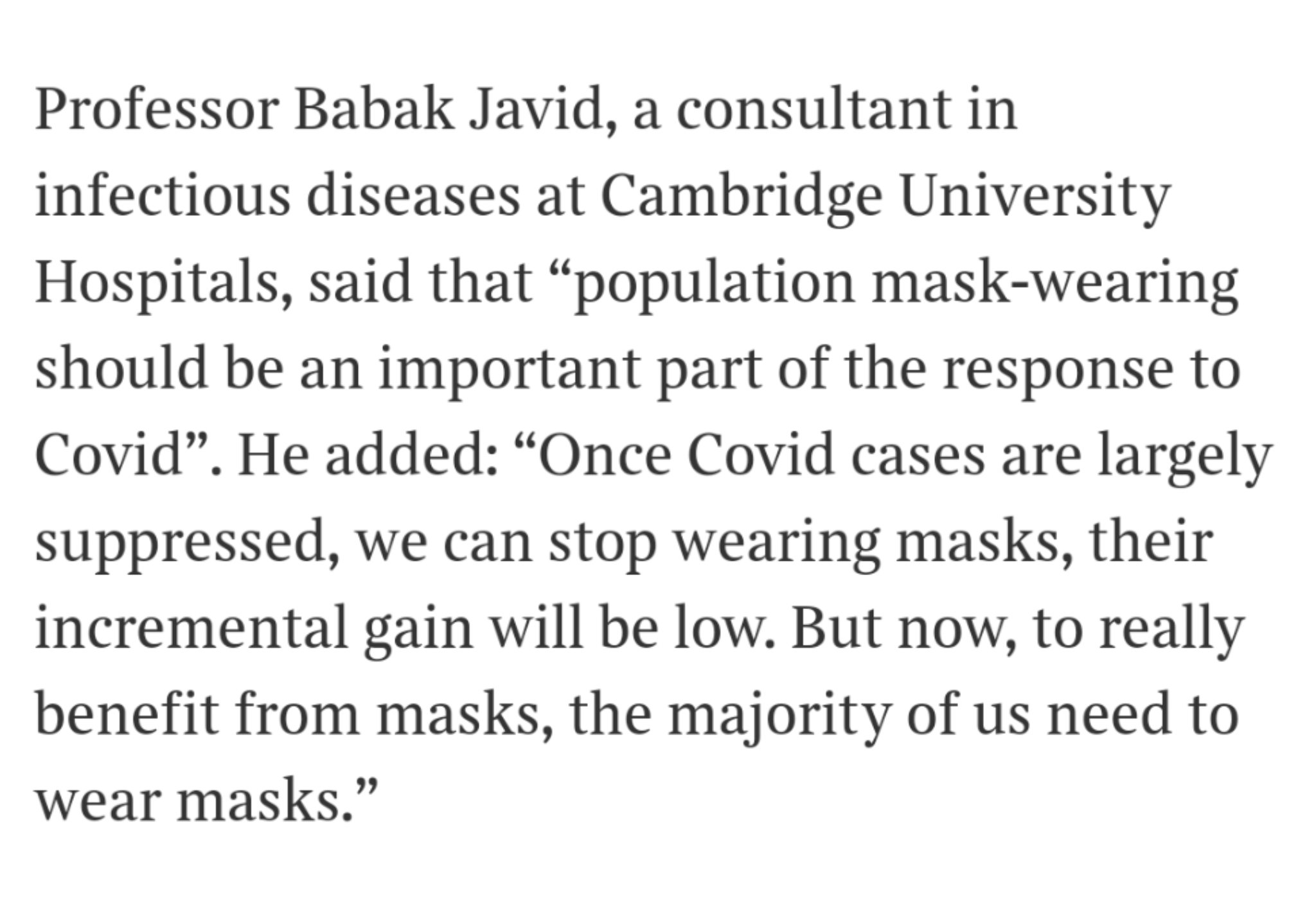

I recently asked on Twitter:

And got reassuring results:

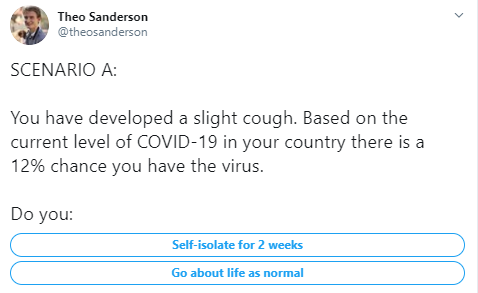

Then I asked another question. Have a think about how you might answer it.

Here is how Twitter responded:

Quite a difference! Not surprising perhaps. The risk of passing on COVID-19 is lower by a factor of 12,000. Nevertheless, I think that the good people of Twitter are wrong, and will explain why a little further down.

The people of Twitter are not alone though, and these sorts of decisions aren’t just thought experiments. The UK government first required people with coughs or fever to isolate themselves on 12 March, long after the virus arrived in the UK. This was part of the government’s strategy of introducing “the right measures at the right time”, and Sir Patrick Vallance gave this as an example, saying that prior to 12 March a very small proportion of people with symptoms would have COVID-19, so it would not make sense to isolate them.

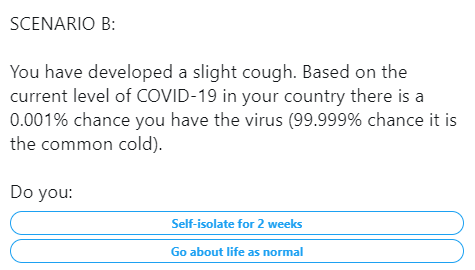

I’ve seen a similar argument made against mask use. After lockdown a small proportion of people will have COVID, the argument goes, so the chance of any particular mask stopping an infection is tiny:

We do this sort of risk analysis all the time. When you go somewhere in a car there is some small chance you could cause an accident in which someone is hurt, but if that risk were 12,000 times higher you would never drive again.

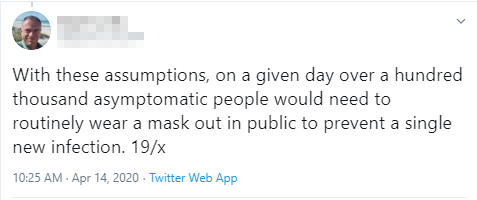

Even some experts appear to agree:

But this argument does not apply for a contagious virus.

Investigating with a simple model

Practically, someone who stays home in Scenario A (when there is a 99.999% chance they have a cold), has the same impact as someone who stays home when there is a 12% chance they have COVID. One way to see this is to simulate an epidemic, and imagine that we institute an intervention for only a week, either early in the epidemic or late in the epidemic.

Let’s consider the mass-masking scenario. Without any interventions, each infected person passes the virus on to 2.5 additional people. We’ll exaggerate the effect of masks and imagine that everyone wearing masks reduces that number (R) to 0.8. In reality this magnitude of effect could only be achieved with a package of many interventions. But it makes it easier to see what’s going on with a graph.

If we plot the epidemic with a logarithmic y-axis, then the steepness of the line is a reflection of how many people each infected person passes the virus to. So if we don’t implement any interventions, this graph goes up with a constant slope.

What happens if we wait until lots of people have the virus, and then bring in masks for 2 weeks to try to stop them passing it on? Well, it’s as you’d expect. The graph goes up as normal, then goes down as R falls to 0.8 for 2 weeks, then starts going up at the same rate again, but reaches a lower point after 80 days than without the two week intervention.

In this case we decided to bring in the 2 week intervention only after at least 1% of people were infected. This seems to make sense. Surely there is no point in making people wear masks when only 0.001% of them have the virus? But let’s check, what happens if we bring in the two weeks much earlier in the epidemic?

It turns out that the two weeks early in the epidemic has exactly the same effect on the number of infections on day 80! What matters is that it has the same effect on R in either case. Even though a far lower absolute number of infected people are wearing masks, R is reduced to 0.8 in both cases.

Ethics: how should we each act in the time of COVID-19?

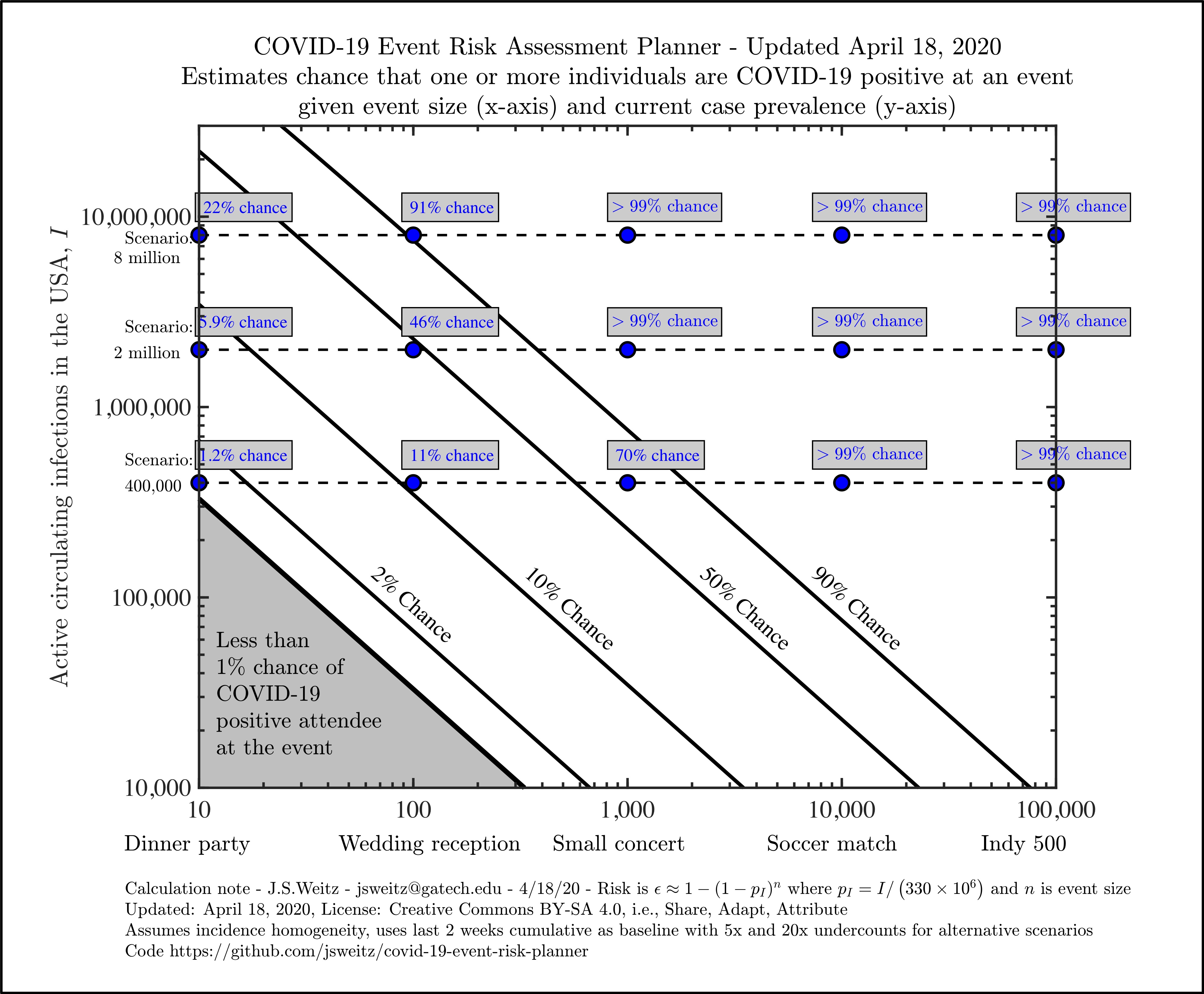

As COVID-19 was spreading in our communities, many people advocated for social-distancing measures. One model for doing this is to think about the absolute chance you have of spreading the virus. For example, someone made a graph to discourage people from holding large events by showing that if there are a lot of infections in the community there is a good chance that large events will cause transmission events:

Interestingly this graph suggests that if one holds a large event when there is a low level of COVID in the community, there is a less negative effect than when there is a high level. But we’ve seen from the models above that this isn’t correct.

So how can we decide how to shape our behaviour? I think it makes sense to follow Kant’s “Categorical Imperative“.

Act only according to that maxim whereby you can, at the same time, will that it should become a universal law.

So imagine if everyone acted as you intend to, and work out what the effect on R would be. If everyone wears masks then, regardless of the level of COVID in the community, R is reduced. If everyone holds large events then, regardless of the level of COVID in the community, R is increased.

In the absence of evidence on seroprevalence and immunity, we must aim to keep R below 1 until we have a vaccine. This will drive the level in the community down to near zero. It will allow vulnerable people to go about their lives as normal. However to achieve these levels we must sustain our measures even as levels in the community drop. Even as we believe that only 30 people in the whole country are infected, we must all wear masks. It’s counter-intuitive, but it will work.